The UNDP and UN Women hosted a collaborative event, “Boosting Women’s Political Participation”, to reflect on the critical role of women’s equal participation in democratic governance in achieving the SDG targets by 2030. The event was part of the Reflections series, which offers lessons based on evaluations collected over the past 10 years of UNDP work. Insights drew from the “Boosting Women’s Political Participation” research paper

The panel began with input from Lisa Sutton, UN Women director, who stressed notable statistics regarding women’s representation in political participation, as they currently account for less than 8 percent of heads of state, and only one in four members of parliament. It was further emphasized that women in politics are needed to challenge entrenched social norms and structural barriers. The main structural barriers which must be confronted are: knowledge barriers, resource constraints, and psycho-social factors.

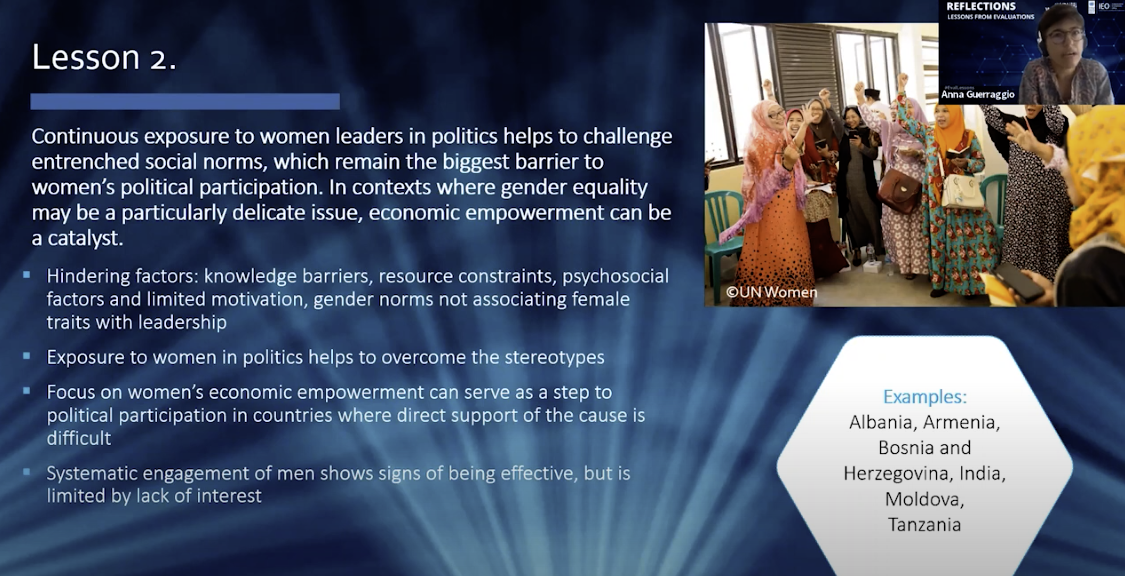

Findings were highlighted by the following programme analysts: Anna Guerraggio, Armine Hovhannisyan, and Victoria Ignat. as most important from the general research produced by the IEO. For example, Lesson #2, states that continuous exposure to women leaders in politics helps to challenge entrenched social norms. A “taste” survey found that the majority of the population still do not trust women as leaders, which presents a significant challenge to women’s political potential. The “provided they are capable” distinction is at work here, wherein people ostensibly do not challenge women leaders as long as they have leadership traits, but it is more difficult for them to identify these traits in women. Two potential strategies were presented to meet this challenge: equipping women with the self-sufficiencies they need to succeed in the political arena, and sustaining men’s participation in these discussions.

Additionally, Lesson #4 was noted, which states that quotas are in fact effective in enhancing women’s political participation when implementation is adequately monitored. An important policy caveat to this finding is that it is important that mechanisms for reporting non-compliance are established. An important policy implication here is that these accountability mechanisms should be tested for effectiveness, an example being that fines for non-compliance are typically ineffective.

Finally, Lesson #5 was highlighted, which starts that the link between women’s participation and promotion of inclusive gender politics. Generally, political processes should focus on being inclusive and gender responsive, with a particular focus on institutional procedures. Intersectionality and the inclusion of all genders is an important component in this piece.

Representatives of Armenia and Moldova noted the success of their countries in ramping up women’s political participation. In Armenia, it was found that strengthening the combined role of women in political, social, and economic dimensions was most successful. Policy has focused on women as agents of change, who develop knowledge of economic development and other skills, from which there is eventually a “snowball” effect. Regarding Moldova, it was one of only 2 countries in the world where a woman is head of state and head of government. This was attributed to their successful enforced long-term interventions, specifically gender quotas for parliamentary and local elections. It was recognized that the success of these quotas has a caveat: capacity-building must be accompanied by other measures which help to safeguard their effectiveness. These include: men’s sustained involvement, electronic measures which combat violence against women in politics, and continued engagement with political parties.

These findings regarding women’s political participation are exciting, and indicate that there are cases where meaningful policy implementations, such as gender quotas and promoting inclusion in political processes.